No Before Times to Be Had: Part Nine

We are reviewing some things you need to do to prepare for a life of pivoting acceptance and today we will look at item two:

Work on mental and emotional issues now

Rest

Critique and adjust your weltanschauung (veltan-shao-ung)

As I mentioned last time, rest is something almost none of us is taught how to do. We all sleep, with varying levels of success, but sleep is only one piece of rest. Many of us also know how to numb, defer and distract. Again, these things can have a part to play in rest at times as well, but they are not the core piece of resting.

Rest is synonymous with the words: relax, refresh and recover. Rest is not prioritized in our modern world.

Rest, at its core, is an unscheduled and yet thoroughly engaging space for your brain. It encompasses flow, as defined by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi.

It is the parasympathetic state of our autonomic nervous system. It should be noted that various chronic illnesses make it much harder to enter into this state and there is some interesting work being done thanks to the deluge of current and upcoming long-COVID we will see in our society: Bye-Bye Fight of Flight? Hello Better Blood Flows? Stellate Ganglion Blocks Long COVID and ME/CFS/FM/POTS.

The thing is, these kinds of treatments are not cures any more than any symptom-supressing drug is a cure. As always, these things can all be very necessary for quality of life for so many, but they do not negate the value of becoming more of an expert in conjuring up a restful state no matter what your path of treatment might be.

The medulla oblongata of the brain stem is the control centre for the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamus oversees that control. That is a highly simplistic and therefore somewhat inaccurate description of course.

If you have a chronic illness you will likely need to be a more experienced practitioner of rest than someone who is ostensibly well. You will have to devote more time to it and will need likely a fair amount of trial and error to figure out what creates relaxation, refreshment and recovery for you in particular.

I will get this out up front now: exercise is not a restful endeavour for those with chronic illness. Yes I know, it is heavily recommended for everything but let us be clear on this—recommendations for physical activity go back millennia and all the research of the twentieth and twenty-first century on the topic looked at the preventative facets of exercise and the onset of disease. When it comes to exercising with disease there is very little to go on.

With the exception of heart disease in men where there is specific research correlating exercise with the reduction or reversal of that disease state, many disease states are either unaffected by exercise or, very importantly, worsened by exercise.

I wrote Exercise Two: Insidious Activity several years ago to address the issues of exercise for those with eating disorders, however much of the material synthesized there is relevant to any chronic illness you would care to name.

The damage done to countless individuals, thanks to the ‘outcomes’ of the PACE trial, who have post-viral syndromes (ME/CFS/POTS and now long-COVID) is now well known and yet many practitioners still persist with its guidelines—namely graded exercise therapy. The trial was riddled with changes in criteria, conflicts-of-interest, informed consent problems and questionable selection of patients. You can check out Bad science misled millions with chronic fatigue syndrome. Here’s how we fought back for a good review on how all the flaws were uncovered.

Your practitioner may prescribe exercise, but be very wary of what, if any, research or evidence they might be using to recommend that for you.

If you have any chronic condition that is messing with your autonomic nervous system in any way, then exercise will not create a post-exertion restful state at all. And a word to those with eating disorders, keep in mind that the hypothalamus is right there in the definition of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. And there is a paper that has assessed the commonality of chronic fatigue syndrome, anorexia nervosa and major depression in the disruptions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Remember, the hypothalamus is overseeing that autonomic nervous system.

But getting out in nature, some fresh air, sitting on a deck or porch for a bit—these things can support your practice of rest. As I mentioned in the Exercise Two: Insidious Activity paper:

“My favorite study on this topic is Elizabeth Nisbet and John Zelenski’s ingenious trial of getting subjects to forecast the benefits they might experience by crossing the campus via the outdoor pathways, or an indoor tunnel-based path to get to classes:

“…we found that although outdoor walks in nearby nature made participants much happier than indoor walks did, participants made affective forecasting errors, such that they systematically underestimated nature’s hedonic benefit.” ”

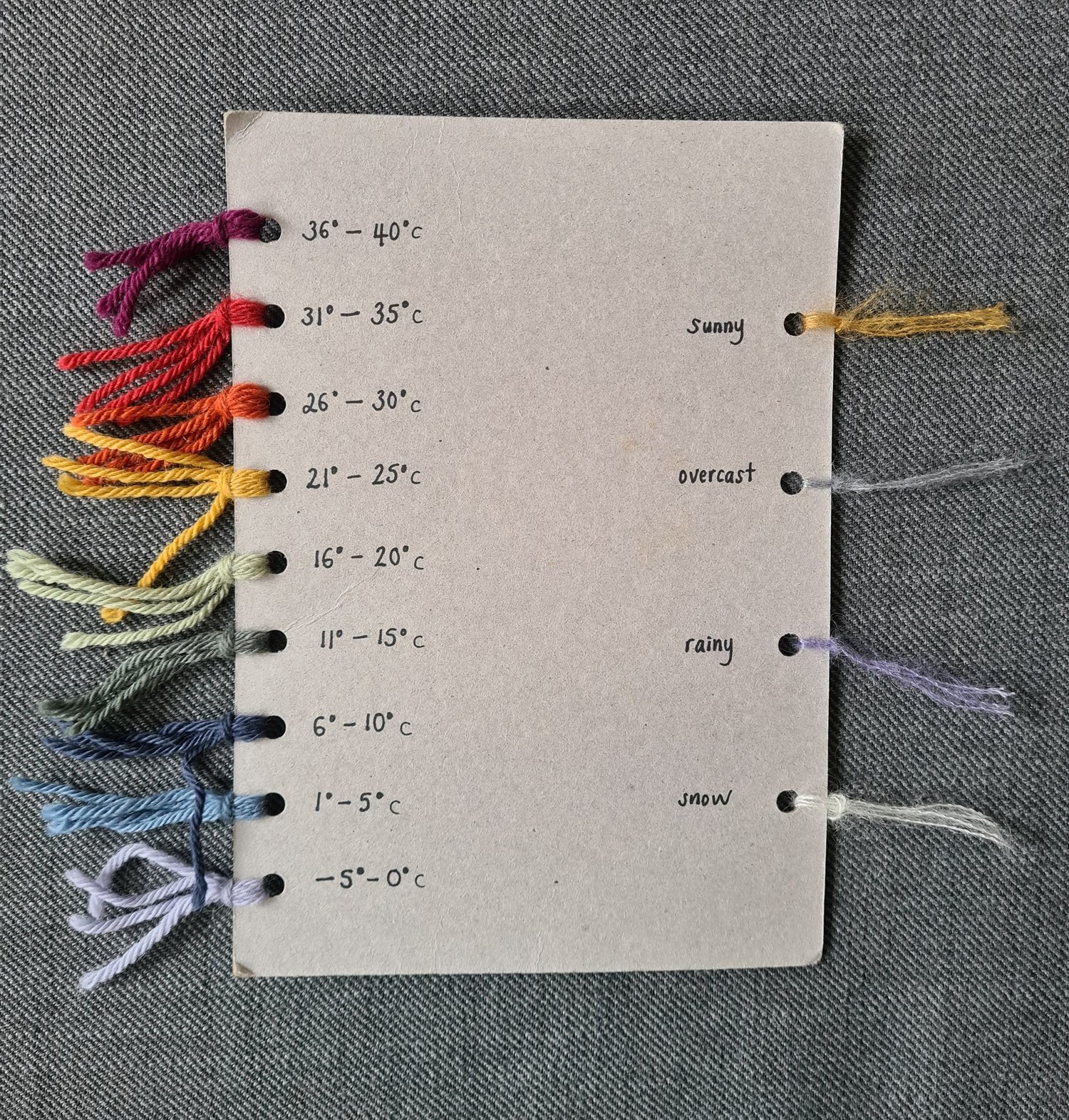

I have yet to get my hands on Josie George’s A Still Life [ed. 2024, have done so and loved it!] but I follow her on Twitter and intend on getting her book to read this year. This is someone who has figured out, through a lot of trial and error, how to induce restful states for herself while navigating significant chronic illness. One thing she does is she creates a weather scarf. She knits but she suggests you could do this any way you would like: cross-stitch, embroidery, paper craft, colouring in strips of paper. She chooses her colour palette at the beginning of the year:

Her approach covers off two techniques for developing restful states: observing weather and nature as well as using your hands to make something.

“Because the use of arts and crafts in occupational therapy has gone in phases and is currently half-embraced and half-shunned, it has never received thorough scientific assessment. Sinikka Pollanen synthesizes what data exist in her published report: Craft as context in therapeutic change. Canadian Karen Ribeiro previously covered off a similar review in Occupation-as-means to mental health: A review of the literature, and a call for research.”

To access the link to the work of Sinikka Pollanen and Karen Ribeiro, see the paper on EDI Exercise Two: Insidious Activity

During our recent (somewhat ongoing) cold snap here, so many people on social media were focused on how to keep the hummingbird feeders going so that our over-wintering hummingbirds could manage to get through the cold. Some had multiple feeders they could swap out through the day, others had elaborate insulation and old (incandescent/warming) Christmas lights to keep the feed above freezing and everyone was sharing how their hummers were doing. I do not have my feeders set up this year (thankfully this is a heavy feeder area so I know the hummers are covered off).

Watching hummingbirds is restful for many of us. Rest is generally unstructured and engaging without requiring a level of concentration you find frustrating or debilitating. If reading requires too much concentration, consider audio books as a way to engage your imagination without having to navigate focus issues. Reading children’s books is great when your concentration has taken a hit due to pain and discomfort. I have read a lot of the brilliant Kate DiCamillo’s books and one of my favourites is The Magician’s Elephant.

I do not know exactly how your rest practice should unfold but as we enter a new year it is a good time to turn your attention to the cause.

Next week in the final Part Ten of the series we will look at weltanschauung.