Trauma-Informed Care

Let’s take a long overdue look at trauma-informed care, or trauma-informed practice, as it relates to receiving any outpatient or inpatient medical and/or mental health care for someone with an eating disorder (or other chronic illness).

I was trained in trauma-informed practice by two leading practitioners, a clinician/researcher from Seattle and a mental health expert on the advisory council for the development of trauma-informed practice in BC. And while it could be viewed as yet another initiative in medical and mental healthcare delivery settings that is destined to be full of empty promises, and the literature leans this way too I’m afraid, there is value in you knowing what it is, and isn’t, if you are someone navigating medical and/or mental health care settings as a patient or family member of a patient.

The history of TIC/TIP is multi-pronged and it is very interwoven with the history of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

TIC/TIP: Interwoven with PTSD and ACEs

We have known for centuries that experiencing or witnessing highly distressing events can lead to a cluster of intrusive and disturbing thoughts and feelings long after the event has occurred. Samuel Pepys described these symptoms after the 1666 Great Fire of London. [1]

Through WWI it was known most commonly as shell shock, and then post-traumatic stress disorder by the 1970s following on from the Vietnam War. Inevitably from there it found its way into the DSM in 1980. In the checklist criteria for PTSD the “existence of a recognizable stressor that would evoke significant symptoms of distress in almost everyone,” [2] was needed to receive the diagnosis.

In 1992, Judith Herman identified a notable gap in the diagnostic criteria of PTSD:

“…the protean sequelae of prolonged, repeated trauma. In contrast to a single traumatic event, prolonged, repeated trauma can occur only where the victim is in a state of captivity, under the control of the perpetrator. The psychological impact of subordination to coercive control has many common features, whether it occurs within the public sphere of politics or within the private sphere of sexual and domestic relations.”

And so was born the diagnosis of complex PTSD (CPTSD, cPTSD, or C-PTSD) in recognition of chronic long-term exposure to trauma.

Then in 1998 the CDC-Kaiser Permanente adverse childhood experiences study was published.

The CDC-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experiences study involved 17,000 subjects and revealed strong correlations between childhood trauma and negative outcomes in adulthood. People with four adverse experiences in childhood (ACEs) were seven times more likely to be alcoholics as adults than people with an ACE score of zero. People with an ACE score above six were 30 times more likely to have attempted suicide. ACEs have a dose-response relationship for creating physical, mental and substance use issues in adulthood. ACEs are common and close to 40% of the original study sample reported two or more ACEs. [4]

From 1998 onwards the flood gates were opened looking at all the poor physical and mental health outcomes for those with high ACEs scores throughout the world: cancers, autoimmune and gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular disease, STDs, suicide, psychosis, PTSD, mental disorders, and premature illness and death. [5] It is bleak. So bleak, that if you take the ACE-Q (adverse childhood experiences questionnaire) and find you have more than zero as a score, you might feel quite deflated.

However, there are positive childhood experiences (PCEs) as well as positive adult experiences (PAEs) that will lower the impacts of ACEs. We are not one-dimensional beings of course.

PCEs may include:

“…childhood peer support, a healthy school climate, and neighborhood safety were especially protective against multiple adult health conditions, including for ACE exposed individuals.”

Sometimes PCEs and PAEs are referred to as counter-ACEs and educational attainment has been shown to be a strong counter-ACE. [7] PAEs involve things that are identified as “turning points” and include a supportive primary intimate relationship, or a sense of belonging to a community. [8]

Yet as with so many other things I’ve brought up on this site over the years, not everything is within an individual’s influence or control: childhood maltreatment (adverse experiences) are consistently and strongly associated with poverty. [9] In other words, were societies to attend to poverty on a systemic level, then high levels of adverse childhood experiences would lessen in prevalence in our populations even absent individual intervention.

Diagnoses of PTSD or cPTSD capture many of the symptoms associated with a history of trauma, but of course not all those with a history of trauma (high ACEs score or experiencing or witnessing an extremely distressing event) necessarily develop cPTSD or PTSD.

Prevalence of ACEs scores among the broad population break down as follows:

“The pooled prevalence of the five levels of ACEs was: 39.9% (95% CI: 29.8-49.2) for no ACE; 22.4% (95% CI: 14.1-30.6) for one ACE; 13.0% (95% CI: 6.5-19.8) for two ACEs; 8.7% (95% CI: 3.4-14.5) for three ACEs, and 16.1% (95% CI: 8.9-23.5) for four or more ACEs. In subsequent moderation analyses, there was strong evidence that the prevalence of 4+ ACEs was higher in populations with a history of a mental health condition (47.5%; 95% CI: 34.4-60.7) and with substance abuse or addiction (55.2%; 95% CI: 45.5-64.8), as well as in individuals from low-income households (40.5%; 95% CI: 32.9-48.4) and unhoused individuals (59.7%; 95% CI: 56.8-62.4). There was also good evidence that the prevalence of 4+ ACEs was larger in minoritized racial/ethnic groups, particularly when comparing study estimates in populations identifying as Indigenous/Native American (40.8%; 95% CI: 23.1-59.8) to those identifying as White (12.1%; 95% CI: 10.2-14.2) and Asian (5.6%; 95% CI: 2.4-10.2). Thus, ACEs are common in the general population, but there are disparities in their prevalence.”

Importantly, prevalence shifts up to higher ACEs scores when you look at sub-populations such as those with mental health issues, and/or housing insecurity and/or substance use issues.

History of TIC/TIP

Helen Bergman, Maxine Harris and Roger Fallot, founders of Community Connections in DC in the 1980s, interviewed and then analyzed the responses of 99 predominantly African American women struggling with serious mental health issues.

“[Their] analysis revealed that the degree of trauma, as measured by recentness, frequency, and number of types of exposure to violence, was positively associated with the severity of a broad range of psychiatric symptoms. The authors therefore concluded that there was an urgent need for services that would include consideration of the impact of trauma in the lives of women who are homeless.”

Notably, these women viewed the abuse and violence they had received, and continued to receive, as normal and not their primary problem. They came to practitioners with complaints of physical or mental symptoms. [12]

From there, Harris and Fallot developed the Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) with four assumptions:

Perceived dysfunctional behaviours and/or symptoms can be legitimate coping responses to trauma.

Women exposed to childhood trauma frequently do not develop typical adult coping skills because of the impact of trauma on development.

Sexual and physical abuse sever core connections to women’s families, communities, and sense of self.

Women who have been abused repeatedly feel powerless and unable to advocate for themselves. [13]

In fairly short order, the two distinguished between trauma treatment services and trauma informed services. Treating the symptom suite that arises from exposure to trauma is distinct from creating an environment that recognizes and accommodates the symptoms associated with trauma exposure.

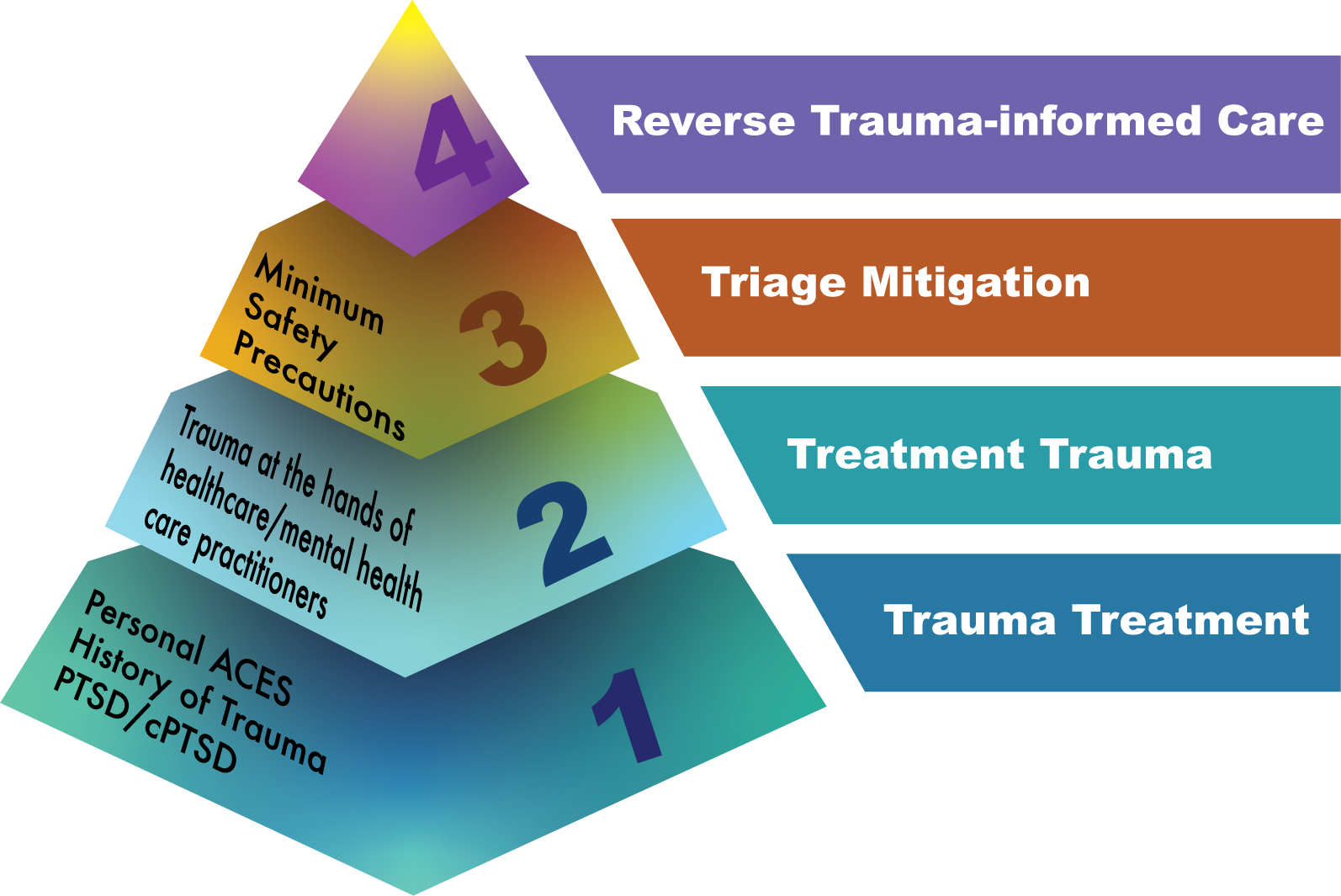

Enter Dr. Sheela Raja and colleagues who did a review of the literature on trauma-informed care in medical settings and created a model for how TIC might be applied to maximize patient engagement. They transformed the tenets of TIC into a pyramid:

Figure 1. [14]

Trauma informed practice or trauma-informed care is not treatment for trauma. TIC/TIP is the application of universal precautions and does not require of the practitioner that they know of, or screen for, any history of trauma. Subsequent models and frameworks recognize the need for practitioners to understand their own history when applying universal precautions (TIC/TIP) and I’ll get to that later in this piece.

How Do Traumatized Patients Feel and React?

Traumatized patients are not a monolith and don’t have just one or even two dominant ways of feeling and reacting.

Trauma may overwhelm a person’s ability to integrate experiences. I have discussed elsewhere the fact that several researchers in the field of PTSD believe that while we all have post-traumatic stress responses to extremely distressing events, the response develops into a disorder precisely because the stress reaction gets “stuck” and there is not an integration into long term memory and sense of self, thus resulting in ongoing symptoms that persist to become the recognized disorder.

Extended exposure to trauma leads to measurable changes in the brain. The amygdala responses dominate (fight/flight/freeze) and this makes frontal lobe involvement much more difficult to bring on line. For patients with a history of trauma, this may involve hyper-vigilance, alterations in consciousness (dissociative states), difficulty regulating emotions, difficulty making decisions, slowed thinking, dislike of ambiguity and blame (self or other directed). Physical symptoms will involve pain, sleep disruptions, illnesses and substance use dependency.

Dr. Diane Yatchmenoff of the Regional Research Institute Portland State University, identified some of the behaviours that might arise for a patient with a history of trauma:

Seems spacey or "out of it." Has difficulty remembering whether or not they have done something.

Complains that the system is unfair, that they are being targeted or unfairly blamed. Combative with authority.

Makes appointments but doesn’t show up; compliant on the surface but not ‘engaged.’

Doesn’t tell the truth.

Changes their mind about what they want and can’t make up their mind. [15]

How Do Traumatized Practitioners Feel and React?

This was one of my main areas of focus when I worked in complex mental healthcare in BC. While it was generally accepted that practitioners in both the health and mental health care fields are overworked, stressed, burnt out and struggling, most organizations and practitioners themselves fail to address this foundational need to “heal thyself” before attempting to heal others.

“We have organizations that come to resemble the people we’re trying to help. ”

This area is a bit of a rat’s nest. Firstly, there are the ACEs, so individuals who have a childhood history of abuse have a propensity to choose a career in direct care in the medical or mental health fields. Secondly, there is the development of PTSD or cPTSD associated with the career itself. Both ACEs and PTSD or cPTSD result in the measurable changes to the brain listed above, resulting in amygdala-driven and cognitively-impaired practitioners.

“ACEs among health and social care workers were frequently reported and occurred more often than in the general population. They were also associated with several personal and professional outcomes, including poor physical and mental health, and workplace stress.”

The prevalence of PTSD is in the range of 16-20% for physicians (when compared to a lifetime risk of 6.8% for the population at large). [18] Physicians with higher ACEs scores were more likely to report burnout. [19] To clarify, “burnout” is a set of reactions to long term stress where the stressors are of an ongoing nature and are out of the individual’s control. Trauma is a stressor out of the individual’s control and is often of an ongoing nature as well. Therefore, burnout is simply yet another cluster of responses to trauma equivalent to PTSD or cPTSD and the literature confirms that practitioners with ACEs are more likely to develop burnout and PTSD.

So how do burned-out/higher ACEs/PTSD-impacted practitioners feel and react?

There is the fully anticipated outcome of their amygdala-heavy and cognitively impaired status: medical error. Physician burnout doubles the risk of medical error. There are also longer recovery times for patients and lower patient satisfaction associated with physician burnout. [20]

But it took me some time to actually arrive at answering the question: how do practitioners with a history of trauma feel and react while performing their professional duties?

The reason it was difficult to get at an answer is due to the fact that practitioner populations are predominantly studied either as a self-contained pod, or as a population reacting to the patient population. In other words, their performance as professionals is only assessed in so far as it impacts themselves, their peers, or the organization.

In attempting to look at patient abuse at the hands of practitioners, searches will come up with practitioner-on-practitioner abuse and bullying, or patient-on-practitioner abuse where the patient is the abuser. There is a significant gap in the literature around practitioner-initiated bullying and abuse of patients. As healthcare is a heavily self-regulated industry, this is not surprising.

Let’s circle back for a minute on how patients with a history of trauma feel and react:

“Without helpful affect regulation skills people who are traumatized may have to rely on tension reduction behaviors— external ways to reduce triggered distress.”

Now referred to more commonly as distress-reduction behaviours (DRBs) instead of tension reduction behaviours, these behaviours drive interactions for patients with trauma and for practitioners with trauma.

However, the power differential shapes how distinctly DRBs are enacted by a patient when compared to a practitioner.

“In evaluating a given new environment or event, an organism is acutely sensitive to indicators of potential threat. Risk appraisal research over the last two decades has shown that the process of evaluating risk involves intuitive judgments...based on [emotional] responses to the situation and expectations about possible outcomes derived from past experience.”

While a practitioner is usually not working in a new environment (and the patient in many cases is in a brand-new environment to them), the potential threat for a practitioner is most commonly the new patient in the room.

Here’s how practitioners tend to behave when they are dealing with a history of trauma:

Seems “dead-eyed." Cannot connect to patients. Sees patients more as a series of parts and tasks to accomplish.

Is either impatient with patients (lots of sighs, expressions of frustration and disgust) or is largely unresponsive with a flat affect and just goes through the motions.

Establishes early dominance with sing-song verbal directives (treating the patient as a child) and/or moving into the patient’s personal space without permission.

Minimizes patient requests for information and help: outright ignores, or is dismissive and disdainful.

Escalates quickly if there is any perceived threat to their superior status resulting, most commonly, in the removal of privileges for the patient (in whatever way that might be defined). Blames the patient.

When these behaviours go up against the behaviours of a patient with a history of trauma things go wrong very, very quickly. Unfortunately, the results tend to re-traumatize both the practitioner and patient, thereby further reinforcing harm in all future interfaces.

Traumatized practitioners are very dangerous to all patients. What is unique to traumatized practitioners, and not enacted by traumatized patients due to the power differential, is the application of torture to alleviate symptoms of trauma. Yes, we’re going there.

What do I mean when I say “torture”?

“…psychological manipulations, humiliating treatment, and forced stress positions, does not seem to be substantially different from physical torture in terms of the severity of mental suffering they cause, the underlying mechanism of traumatic stress, and their long-term psychological outcome.”

The studies are very few and far between, but there was one study on child soldiers of war that showed their symptoms of PTSD associated with all the trauma they had witnessed and perpetrated was alleviated when they tortured their captors. I’ve not been able to relocate that study although I referenced it in a report (to which I do not have access now obviously for privacy reasons) that I generated when working in complex mental healthcare. However, I have been able to locate one other study that confirmed soldiers who tortured prisoners of war had a distinct clinical presentation of PTSD, when compared to those prisoners of war that they had tortured. PTSD scores were significantly higher for the prisoners of war. [24]

The threat for a traumatized practitioner is the patient. That is often not a false threat as many practitioners have been verbally and physically abused by patients. Patients and families abusing practitioners is drastically on the increase and unlikely to abate in the foreseeable future. [25] The rates of violence are a reflection of the inhumane systems in which care is delivered.

“We posit that stigmatized targets elicit especially high levels of anticipated exhaustion because of the conflicting goals they activate during empathic situations—that is, the need to balance compassion against concerns about physical risk, contamination, and inefficacy of helping—leading perceivers to engage in defensive dehumanization.”

The above quote comes from a study reviewing two experiments to arrive at a rather novel interpretation of why humans dehumanize other humans. Most frameworks used to explain dehumanization suggest that it’s a post-hoc set of behaviours used to both facilitate aggression/torture and rationalize past acts of aggression or immoral behaviour.

“Even without intending to harm others, people may defensively dehumanize stigmatized targets to avoid becoming emotionally exhausted and overwhelmed by the act of helping these individuals.”

I would suggest that a better term for this kind of dehumanization is pre-emptive or anticipatory stigmatization rather than defensive stigmatization and that this is the dominant form of distress-reduction behaviour we will see from traumatized practitioners. The process by which a patient receives maltreatment and torture at the hands of a practitioner is as follows:

The practitioner with a history of trauma identifies the patient as the novel threat in the room.

The practitioner pre-emptively dehumanizes that patient anticipating that helping would be an exhaustive effort.

The practitioner, no longer seeing the patient as human, will readily torture the patient to further alleviate the practitioner's sense of the patient as a threat.

I will now explain trauma-informed care and practice in the next section as it is expected to be implemented in healthcare and mental healthcare settings. Then I will wrap up this piece by looking at the ways in which a patient might reverse TIC/TIP to alleviate the risks of harm they might face when dealing with a traumatized practitioner.

How is TIC/TIP applied?

A patient is not expected to divulge their own history of trauma in order that they might receive trauma-informed care. As per the pyramid above [Figure 1.], screening for a history of trauma should only be initiated by a fully-qualified social worker or psychologist who specializes in trauma treatment. A facility or service that enacts TIC/TIP uses universal precautions, meaning they assume a history of trauma and apply trauma-informed care to everyone.

Figure 2.

Downloadable PDF of SAMSHA Principles

The SAMSHA Model

The SAMSHA model it the most-used framework for trauma-informed application in service settings. Let’s go through the six guiding principles:

Safety

One of our receiving spaces in one of the hospitals in which I worked, was actually in the basement of an old repurposed building that was scheduled to be demolished (now demolished and a purpose-built facility was opened in its place). It had cement block walls and was windowless save the double-wide fire doors at the bottom of the stairs to enter the area. It had uncomfortable plastic chairs and a standard large plastic foldout table.

The care team and patients worked together to redesign and reimagine the space as, in patient and family surveys, this space was flagged by all as tremendously panic-inducing and threatening.

Physical safety is the base level of offering trauma-informed care: the receiving area, the hallways, the bathrooms, clear signage for directions around the space, etc. It appears as though the evidence supports attending to the physical space as having real value for patients and they are often inexpensive to services to apply them. [28]

The first question (or variation on this) that is asked of patients is: “Is there anything I can do to help make you feel more safe?”

Emotional safety is next. Creating emotional safety involves things like explaining what will be happening before it happens; asking for permission; using clear instructions and checking for comprehension; explaining boundaries and expectations and modelling them.

Trustworthiness and Transparency

Trustworthiness is built upon those emotional safety efforts wherein the practitioner has made the process and expectations clear at the outset and the team is subsequently aligned and able to deliver on those commitments. The team models the behaviours expected of both practitioners and patients alike.

Transparency is a clarity of policies, process and procedures throughout the service such that a patient and their family is well aware of their rights and responsibilities and knows how to seek out further information and have all their questions and concerns readily answered and resolved.

Peer Support

Keeping in mind this particular TIC model is focused on mental healthcare, integrating peers in the support of patients tends to further alleviate trauma reactions as a peer will often be seen as less threatening than facility staff and the reassurance that the peer “knows how it feels,” tends to lower tension and distress for the patient.

Collaboration and Mutuality

Collaboration and mutuality are conscious efforts to flatten of the power differential as much as is feasible. Decision-making is achieved jointly. The patient is involved in goal setting and care planning.

Empowerment, Voice and Choice

Building on the concepts of collaboration and mutuality, the patient is encouraged to build upon their self-advocacy skills. The framework is very much a strengths-based one, respecting that the trauma responses a patient exhibits were ones developed out of tremendous resilience and a will to live.

Cultural, Historical and Gender Issues

The organization actively educates all employees on the systemic elements of trauma across generations. This encompasses the epigenetic impacts of trauma in families as well as the systemic application of discrimination and abuse that generates trauma responses for targeted groups in society.

Here are a few videos showing some examples of what trauma-informed care can look like:

Jennifer S. Greene Trauma-Informed Care Example 1

Jennifer S. Greene Trauma-Informed Care Example 2

Jennifer S. Greene Trauma-Informed Care Example 3

TIC/TIP and You

You will often hear those trained in TIC/TIP say that the development of these skills is summed up by the mental shift from asking “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

As you know from likely reading several of my other posts here, I frame behaviours and traits as attributes that may have beneficial, neutral or detrimental impacts depending on the environment in which you find yourself. I don’t hold that any behaviour or trait can be defined as a universal strength or a universal weakness. Many with a history of trauma internalize their anticipatory and coping behaviours as “I’m a bad person.” Rather than just getting a patient to focus on their strengths, I prefer to have them disengage their sense of value and self from their traits and behaviours altogether. When a patient has survived trauma then their anticipatory and coping behaviours around the threat were incredibly life protective— they are here today. They endured and survived the threat. That they might get triggered in spaces where there is no threat doesn’t make them, or anyone, a bad person. It’s just a behaviour or trait that has been activated in the wrong circumstance. Similar to the misidentification of food as a threat for eating disorders – the threat system is doing its job, just in the wrong situation is all.

I have seen recent chatter on socials from psychologists who view TIP/TIC as just a bundling of what practitioners would do as a matter of course to make a patient feel safe and well cared for.

The thing is, psychologists and social workers are actually trained not just to be trauma-informed, but to apply trauma treatment safely and supportively. However, nurses, physicians, most psychiatrists, occupational therapists, nutritionists and dieticians, care aides, radiologists, food services, cleaning services, patient advocates, paramedics, hospital administrators, lab technicians etc., do not receive any education in psychological trauma during their accreditation processes.

If nothing else comes of TIC/TIP initiatives in healthcare and mental healthcare settings beyond an improved awareness in practitioners that psychological trauma is common and shapes behaviours and coping mechanisms often vilified and stigmatized as “difficult” or “non-compliant,” then I would prefer that outcome over obliviousness.

However, the real failure of TIC/TIP is not focusing it first and foremost on practitioners. Unfortunately, healthcare administration wields initiatives as a way to smooth patient frustration and limit liability rather than as a way to implement the real financial commitment and recovery necessary to heal practitioners: “No, no that could not have happened, all of our practitioners are trained in trauma-informed care.”

I won’t get into all the reasons why our healthcare and mental healthcare services are all in a disintegrating worsening crisis globally (this piece is long enough), instead I will focus on what, if anything, you might do as a patient now you know a bit more about adverse childhood experiences, trauma symptoms and trauma-informed care.

Hierarchy of Trauma-Informed Care from a Patient Lens

If you have a history of trauma and abuse from childhood, then you often end up in a nasty cycle of needing medical and mental healthcare directly as a result of how trauma impacts you psychologically and physically. Then as an inpatient your symptoms of trauma and your coping mechanisms are pathologized and you end up with several diagnoses and psychotropic prescriptions. Furthermore, these spaces are highly triggering for you as they re-enact the utter lack of control and autonomy that you experienced as a child.

There is an insidious narrative within the TIC/TIP training that continues to excuse and deflect the very specific and novel ways in which a patient might be traumatized by abusive treatment in care. The framing of “we don’t want to re-traumatize the patient,” has a subtext that the treatment the patient is receiving is not objectively harmful, abusive or traumatizing, but rather their sensitive history is to blame for interpreting the experience as abusive.

Keeping in mind, we have a disproportionate number of practitioners with high ACEs scores having subsequently developed burnout and PTSD who actively torture patients to alleviate symptoms of trauma in themselves, patients experience brand new trauma in treatment that does not trigger any memories or painful experiences of abuse as a child or adult.

TIC/TIP does not address treatment trauma and the very specific ways in which prior traumatic medical and/or mental health treatment experiences will heighten the level of reactivity and misery for a patient.

Here is an example of re-traumatization (traumatized again):

A practitioner asks a patient to take a seat and offers them a glass of water. For the patient this triggers a memory of how their abusive father would always come into their room at night with the excuse of bringing them a glass of water. Or perhaps being asked to sit down is how their abusive partner starts off every fight that leads to being beaten by that partner.

Here are examples of treatment trauma (traumatized anew in a medical and/or mental healthcare setting):

Undergoing a medical procedure that causes tremendous pain and being told that it is not painful.

Re-hospitalization due to a (separate from initial admission) adverse medical event within 30 days of discharge (impacts about 1 in 5 seniors) and is called post-hospital syndrome. [29]

Post-intensive care syndrome (psychosis, impaired cognition, drastically reduced mobility).

Being roughly handled, having personal intimate space touched without explanation or permission.

Insufficient anesthesia during a procedure.

Being told to change into PJs or gowns that are visibly soiled or do not fit.

Being treated/disrobed/having medical history discussed in a public area due to overcrowding.

Not being given food or water for days at a time usually due to understaffing and rescheduling of procedures.

Being discharged from hospital unsafely (no ride home, inadequate clothing, in pain, inadequate bridging medications, unclear discharge instructions, still medically fragile/vulnerable).

Soiling oneself because there is no safe way to get to a toilet and no one to help.

Experiencing a medical error. The prevalence of adverse events occurring in a hospital stay is 12.4%. [30]

Not advised of experiencing a medical error or the likely outcomes of the error.

I could go on. These are examples of treatment trauma because they can trigger a novel trauma response in those with a history of trauma but also generate a new trauma response in someone with no history of trauma.

I haven’t even touched upon mental healthcare settings with their restraints (usually chemical these days) and significant use of seclusion rooms (solitary confinement).

The literature tends to skew very heavily at trying to develop screening to identify who’s at risk of developing post-hospitalization PTSD which utterly bypasses the opportunities for universal precautions to try to make the experience less traumatizing for all. There is some interesting work being done at least with ICU, as post-ICU PTSD sits at about 20%, in redesigning the experience itself. Large visible clocks and ICU diaries kept by staff and family to help orient the ICU survivor on discharge as the drugs generate hallucinations and leave the patient vulnerable to psychosis. [31]

According to the studies out there so far, there is no way to tell who might develop treatment trauma and it is not correlated to having a history of ACEs or even existing PTSD.

Figure 3.

Figure 3 is the EDI-developed Patient Lens TIC pyramid. Rather than wishing and hoping that health and mental healthcare spaces could robustly enact true systemic trauma-informed care such that you would be protected and supported, here are some things you can do to leverage what is in your control.

Trauma Treatment

First and foremost, if you have a history of trauma, then you will benefit from treatment for that trauma. Ideally you want to get that treatment on your terms in an outpatient environment with a trained clinical psychologist with expertise in PTSD and cPTSD. You will avoid re-traumatization in any future medical or mental health setting if you receive treatment for your underlying trauma while not in those spaces. While you may receive trauma treatment as an inpatient in a mental health setting, the sessions may be too few or depend too heavily upon group sessions and trauma treatment needs more intensive and dedicated focus than most inpatient settings are able to provide.

While prefacing this with the fact that in both cases these YouTubers are not credentialed psychologists, if you approach their channels for information, they are highly regarded by many struggling with PTSD and c-PTSD:

Tim Fletcher

Crappy Childhood Fairy

For an explanation by a clinical practitioner on cPTSD: Recognizing and Understanding Complex PTSD

Here is a well-reviewed guidebook to consider as well: The Post-Traumatic Growth Guidebook: Practical Mind-Body Tools to Heal Trauma, Foster Resilience and Awaken Your Potential

Treatment Trauma

As mentioned before, treatment trauma is common in health and mental health care spaces and we cannot predict who might develop it ahead of time. If you already have treatment trauma, then as with trauma treatment, it’s wise to get psychological counselling before you have to be in any care setting yet again. A practitioner specializing in PTSD will be useful in this case.

Some books that may help in this case:

Surviving Your Hospital Stay: A Nurse Educator's Guide to Staying Safe and Living to Tell About It

Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What is Right for You

Finding and working with a GP who is able to give you the time and space to make medical decisions in partnership will help you deal with your health needs proactively rather than reactively and enhance your sense of agency in medical decision making when perhaps you do need emergent hospitalized care in the future.

Triage Mitigation

Let’s say you haven’t yet got your trauma treatment and/or treatment trauma well in hand and you find yourself in an unavoidable and unplanned healthcare or mental healthcare setting that is stressful and unpleasant.

As soon as you finish reading this long post, consider developing advanced directives for trauma. If you live and work in a geographic area where you have one electronic health record that would be accessed by all healthcare providers in an emergency setting, ask your doctor to put a note in your file that reads: “Patient has a history of trauma. Please apply trauma-informed practice to help them self-regulate.”

Having a professional note on your file that indicates you benefit from practitioners applying trauma-informed care, can act as a priming schema for all practitioners who orient to you by scanning your file first. A priming schema can be explicit or implicit (in this case it is explicit) and it’s a premise in psychology that we store memories in associated and connected “clumps” or units. When one aspect of that unit is activated, all the associated elements are activated alongside it. Even if a practitioner has not been trained in trauma-informed practice, they have enough associated understanding that increased patience and kindness is helpful for stressed patients. And an additional schema primed, in this case, is that a colleague (someone they would consider more reliable or believable) is the originator of the note on how to best approach the patient, thereby possibly lowering the novel threat of that patient to them.

Store a note on your phone, or on a piece of paper that is in your wallet that can be accessed and handed to a healthcare provider. If you are in an agitated spiral you can relay to them your need for their help without having to try to compose yourself enough to say so in the moment. “I have a history of trauma. At the moment I’m struggling to calm myself and really appreciate your help although I can’t express my thanks right at this moment.”

Have a plan in place that a trusted someone in your life can be with you, or come to you, if you have an unplanned emergency and they can support you in your efforts to calm yourself thereby lowering the risk of escalation with healthcare providers.

If you think you might be able to speak in the moment, then practice when you are in a safe space being able to relay on demand: “I so appreciate your patience with me. I have a history of trauma and it gets fired up so quickly. I know the demands on your time are intense but any slowing down or breathing room you can give me for next steps right now is so helpful for me. Thanks.”

The goal in that situation is to survive the experience without further damage. Look for any practitioner on the scene where your instinct tells you that they might hear you.

Often, because the threat system triggers avoidance, it is hard to develop a triage plan because even thinking about being in those emergency settings triggers post-traumatic stress responses. Have someone safe in your life help you to put in place two or three basic mitigations you can apply in the moment (like those listed above or something similar) if it’s distressing to go through the process of preparing them.

Reverse Trauma-Informed Care

Performing reverse trauma-informed care is not something I would ever attempt without having the foundational elements of the Figure 3. pyramid well in hand first. However, it is also something that many, many patients enact instinctively. When an agitated, frustrated and triggered healthcare practitioner enters a patient’s space, many patients can diffuse that escalated energy quickly. They are performing reverse trauma-informed care without being aware of doing so.

The foundation of TIP/TIC is exactly the same whether applied on patients or practitioners: it’s seeing the human being rather than the behaviours that arise in inhumane circumstances.

Reverse TIC is trickier than TIC because the power differential works against the patient not for them. The meta-cognitive effort for a practitioner to self-regulate when a patient is “kicking off” (a term that in and of itself is not trauma-informed) is much less than when the roles are reversed. A practitioner has the ability to remove themselves, call security, enact a code white (an emergency response for a violent person), and subdue the patient in whatever way they deem necessary.

Here are a couple of examples of reverse TIC:

“It’s so busy out there! I appreciate how hard you all work here and so is there anything I can do as your patient to make this go more smoothly or make it easier for you in any way?”

The above example is merely a variation of TIC/TIP safety: “What can I do for you right now to make you feel safe?”

“How is your day going?” can also work wonders when you mean it.

Compliment your healthcare provider on anything, however small, that reflects that you have recognized their care (their strengths). If they are rude, brusque and handle you roughly without permission, maybe at least their hands weren’t cold. If you can find something you genuinely appreciate however small, then voice it.

The vast majority of traumatized practitioners can be pulled back to professional and compassionate interactions when their own humanity is validated. It’s an abject failure of the system that it often must be the patient who validates their humanity and not their own organization and hierarchy, but that is the reality of today’s healthcare.

Meta-cognition is your superpower. Even in an agitated and pained state, it is possible to apologize for your own behaviour that might seem threatening to a traumatized practitioner in that moment. “Wow that friggin’ hurt! I’m sorry that was an instinctive reaction on my part. Are you okay?”

Most escalation that ends with harm involves traumatized practitioners faced with a patient who is setting some personal boundaries (whether they are objectively reasonable or not) that ram up against the practitioner’s need to get stuff done or to simply follow guidelines and procedures that they treat as inviolate and mandatory. Remember, a traumatized person is not a fan of ambiguity and prefers black and white.

If you deal with a practitioner who is unresponsive to reverse TIC and is escalating the situation:

Can you leave? If this is an appointment or consultation and not an inpatient or hospitalized setting, then leave: “Thank you for your time so far but I think we are at the point where we’d both be wasting our time to continue.”

Can you de-escalate safely? If it’s possible to appeal to a timeout, do so: “I can’t leave my room to take a break obviously, but maybe you’d like to go attend to other patients for a few minutes while we both reset as I think we’re just on the wrong foot together right now. I’m sure we can reset and try again in a bit.”

Can you negotiate safely? “I am hearing you that my position on this is not how things are done and you need to follow your guidelines and procedures. I don’t want to make more work for you but I also believe my position is reasonable. Are you okay with us taking this to your supervisor to see if we can arrive at a compromise of some sort?”

Can you call for help? “I would be more comfortable right now with another practitioner, could you ask your colleague to help instead?” If that needs to be backfilled with statements such as “This is a “we” thing – for some reason we are not clicking and I don’t want you to feel like I’m blaming you here because I’m not,” then add something along those lines to ease the message.

Can you survive? With recognition that this is an extremely painful and costly last-ditch approach, if you cannot get safe in the moment then you have to use skills that help you survive in the moment. Don’t react or respond to the abuse as that will place you at increased risk of harm. Focus on the steps to get safe from the point at which the practitioner has left your space.

I want to further emphasize that when you are a member of a targeted and stigmatized group in society, the success you might have in applying reverse TIC is not likely going to be as high as when someone with endowed privilege uses reverse TIC in healthcare and mental healthcare settings. One of the most valuable things you can do when you are someone who has the privilege of whiteness, and even more so white maleness, is to use your ability to apply de-escalation and advocacy with greater success in the service of those who are heavily targeted and stigmatized in our society. Be the one who is present alongside your stigmatized friend when they must navigate healthcare and mental healthcare experiences.

Conclusion

While trauma-informed care is anchored in reams of literature on adverse childhood experiences, post-traumatic stress responses (one-time or complex), the reality is that it is rarely implemented systemically in healthcare or mental healthcare settings. In practice, administrations place the burden of trauma-informed care on individual practitioners as a way to deflect the damage that is done to both practitioners and patients in these inhumane settings. When practitioners are trauma-informed in their dealings with patients, this happens in spite of the organizations in which they work, not because of them.

Healthcare and mental healthcare spaces are traumatizing for practitioners and patients alike. Patients receiving care in these spaces can be re-traumatized, when they have a history of trauma, and they can be traumatized in specific and novel ways whether they have a history of trauma or not. Practitioners have higher-than average rates of histories of trauma and develop both PTSD and cPTSD as a direct result of the trauma witnessed and experienced throughout their careers as well.

Trauma-informed care or practice does not focus sufficient attention on the necessity of practitioners treating their own histories of trauma, nor does it honestly address that medical and mental health treatments actively traumatize patients, and don’t merely trigger memories of past unrelated trauma.

Unfortunately, trauma-informed care in its application today allows for practitioners and their organizations to continue rationalizing the treatment they provide as: “we’re the good guys here.”

As such, an informed and empowered patient has to enter these spaces knowing that they could be re-traumatized and/or traumatized and that many practitioners are dangerous to patients due to untreated histories of trauma, PTSD and cPTSD. If you can apply reverse trauma-informed care as a patient to practitioners it may lessen the risk of re-traumatization and trauma at the hands of those practitioners.

And finally, if you do have a history of trauma from childhood and/or adulthood, just remember that your coping skills that helped you survive that trauma may have resulted in PTSD or cPTSD, but it likely also included post-traumatic growth (PTG).

“While combat exposure often has a number of harmful effects, research has also found that many individuals who live through traumatic events, in some cases the majority (Affleck and Tennen, 1996), report experiencing positive psychological changes. This process has been termed posttraumatic growth (PTG). In such cases, the experience of trauma may lead to a higher level of functioning or well-being (Calhoun and Tedeschi, 2014, Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995, Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004), or enable the individual to respond more adaptively to future stressors (Tsai et al., 2016a). Research on PTG has been conducted in a wide variety of populations, including cancer patients and their partners and children, parents of surgical patients, earthquake and hurricane survivors, survivors of childhood sexual abuse, survivors of motor vehicle collisions, women victims of sexual assault, patients with PTSD, ex-prisoners of war, students, and military veterans (Schubert et al., 2016). These findings suggest that PTG is not uncommon among a broad range of trauma survivors, particularly among those with PTSD.”

The most painful aspect of a care experience gone wrong for the patient is that it breaks the expectation of care altogether. For those of you with a history of trauma who feel daunted by how traumatizing healthcare and mental healthcare spaces are these days, just remember, you have knowledge and skills not available to someone who still believes these spaces are safe. Counterintuitively, you have the ability to keep yourself safe when you know you are not safe.

O'brien LS. Traumatic events and mental health. Cambridge University Press; 1998 Feb 19. p.7.

http://traumadissociation.com/ptsd/history-of-post-traumatic-stress-disorder.html#dsm-iii

Herman JL. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of traumatic stress. 1992 Jul;5(3):377-91.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine. 1998 May 1;14(4):245-58.

Zarse EM, Neff MR, Yoder R, Hulvershorn L, Chambers JE, Chambers RA. The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Medicine. 2019 Jan 1;6(1):1581447.

La Charite J, Khan M, Dudovitz R, Nuckols T, Sastry N, Huang C, Lei Y, Schickedanz A. Specific domains of positive childhood experiences (PCEs) associated with improved adult health: A nationally representative study. SSM-Population Health. 2023 Dec 1;24:101558.

Giovanelli A, Mondi CF, Reynolds AJ, Ou SR. Evaluation of Midlife Educational Attainment Among Attendees of a Comprehensive Early Childhood Education Program in the Context of Early Adverse Childhood Experiences. JAMA Network Open. 2023 Jun 1;6(6):e2319372-.

Crandall A, Magnusson BM, Barlow MJ, Randall H, Policky AL, Hanson CL. Positive adult experiences as turning points for better adult mental health after childhood adversity. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023 Aug 3;11:1223953.

Skinner GC, Bywaters PW, Kennedy E. A review of the relationship between poverty and child abuse and neglect: Insights from scoping reviews, systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Child Abuse Review. 2023 Mar;32(2):e2795.

Madigan S, Deneault AA, Racine N, Park J, Thiemann R, Zhu J, Dimitropoulos G, Williamson T, Fearon P, Cénat JM, McDonald S. Adverse childhood experiences: a meta‐analysis of prevalence and moderators among half a million adults in 206 studies. World psychiatry. 2023 Oct;22(3):463-71.

Goodman LA, Dutton MA, Harris M. The relationship between violence dimensions and symptom severity among homeless, mentally ill women. Journal of traumatic Stress. 1997 Jan;10(1):51-70.

Sciolla AF. An overview of trauma-informed care. Trauma, resilience, and health promotion in LGBT patients: What every healthcare provider should know. 2017:165-81.

ibid.

Raja S, Hasnain M, Hoersch M, Gove-Yin S, Rajagopalan C. Trauma informed care in medicine: current knowledge and future research directions. Family & community health. 2015 Jul 1;38(3):216-26.

https://traumainformedoregon.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Intro-to-Trauma-Informed-Care.pdf

ibid.

Mercer L, Cookson A, Simpson-Adkins G, van Vuuren J. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences and associations with personal and professional factors in health and social care workers: A systematic review. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy. 2023 May 4.

Vance MC, Mash HB, Ursano RJ, Zhao Z, Miller JT, Clarion MJ, West JC, Morganstein JC, Iqbal A, Sen S. Exposure to workplace trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among intern physicians. JAMA Network Open. 2021 Jun 1;4(6):e2112837-.

Yellowlees P, Coate L, Misquitta R, Wetzel AE, Parish MB. The association between adverse childhood experiences and burnout in a regional sample of physicians. Academic psychiatry. 2021 Apr;45:159-63.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of internal medicine. 2018 Jun;283(6):516-29.

Briere JO. Treating the long term effects of childhood maltreatment: a brief overview. Psychotherapy in Australia. 2004 May 1;10(3):12-8.

Marshall RD, Bryant RA, Amsel L, Suh EJ, Cook JM, Neria Y. The psychology of ongoing threat: relative risk appraisal, the September 11 attacks, and terrorism-related fears. American Psychologist. 2007 May;62(4):304.

Başoğlu M, Livanou M, Crnobarić C. Torture vs other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment: is the distinction real or apparent?. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007 Mar 1;64(3):277-85.

Kozaric-Kovacic D, Ljubin T, Marusic A. Combat-experienced soldiers and tortured prisoners of war differ in the clinical presentation of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nordic journal of psychiatry. 1999 Jan 1;53(1):11-5.

Vento S, Cainelli F, Vallone A. Violence against healthcare workers: a worldwide phenomenon with serious consequences. Frontiers in public health. 2020 Sep 18;8:570459.

Cameron CD, Harris LT, Payne BK. The emotional cost of humanity: Anticipated exhaustion motivates dehumanization of stigmatized targets. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2016 Mar;7(2):105-12.s

ibid.

Muskett C. Trauma‐informed care in inpatient mental health settings: A review of the literature. International journal of mental health nursing. 2014 Feb;23(1):51-9.

Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome–a condition of generalized risk. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Jan 1;368(2):100.

San Jose-Saras D, Valencia-Martín JL, Vicente-Guijarro J, Moreno-Nunez P, Pardo-Hernández A, Aranaz-Andres JM. Adverse events: an expensive and avoidable hospital problem. Annals of medicine. 2022 Dec 31;54(1):3156-67.

Greenberg J, Tsai J, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Can military trauma promote psychological growth in combat veterans? Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021 Mar 1;282:732-9.